Sexual harassment in Lebanon: A crime that goes unnoticed

In late 2020, Lebanon finally passed a law making sexual harassment a crime. But while the landmark legislation, called Law 205, is considered a step forward, human rights groups say it fails to meet international standards and protect women who dare to speak up.

Lara* was sleeping at home at 4am when she heard a knock on her door.

“I woke up frightened, and had no idea who was at my door in the middle of the night,” she said. “I asked, ‘Who is it?’ from behind the closed door. Marwan Habib, who was a neighbour at the time, responded, asking if he could sleep at my place since he had lost his keys.”

“I refused and asked him to leave, but he wouldn’t. I told him I would report him but he laughed, telling me to relax and spend the night with him. Never in my life have I felt this humiliated and since then, a part of me, [my sense of security] was shattered,” she added.

Lara* is one of many women who fell victim to Habib. In late 2019, more than 50 women reported being harassed by him and one even said she was raped. In 2020, Karim Majbour, a Lebanese lawyer, filed a lawsuit against him.

“The things Habib has done would have landed him in prison for years. A woman on television even reported that he raped her. The problem isn’t that the system couldn’t convict him – it didn’t want to,” Majbour told FRANCE 24.

“Since in Lebanon a harasser can escape punishment, survivors had to wait for another country to punish him in order to feel they’ve earned some justice,” he added, citing Habib’s conviction earlier this month in Miami, Florida, for attempting to sexually assault a woman in her own hotel room.

The Miami police report stated that the defendant was known to “pursue females in order to have sex or date them, even after they advised him to stop doing so on multiple occasions.”

Habib is being held without bond due to an immigration hold and faces deportation back to Lebanon, according to US media reports.

A new law with ‘many loopholes’

In late 2020, Lebanon adopted Law 205, which defines sexual harassment as a form of misdemeanor, stopping short of calling it a felony. Majbour said the law was submitted in 2014, but was overlooked by parliamentarians until it was passed six years later due to pressure exerted by women – notably in response to Habib’s crimes.

“A harasser is someone who has the potential to become a rapist. That is how I see it,” Majbour said. “Habib is not the only harasser in Lebanon, and while this law is a step forward, it has many loopholes.”

Majbour says the law downplays the psychological and physical affects harassment can have on survivors.

Additionally, the law does not protect the women who file lawsuits. Majbour explained that if, for example, a woman reports harassment in the workplace, the law does not protect her from retribution.

Moreover, the punishment for what the law terms a “misdemeanor”, especially when it occurs in a public space, remains insignificant.

Under the law, sexual harassment in a public space is punishable with up to one year in prison and/or fines up to 10 times the minimum wage. If harassment happens in the workplace, the fine is increased and could reach up to 50 times the minimum wage and a prison term of up to four years.

“In its current form, the law seems only to serve the interest of the government in presenting Lebanon positively to the international community. However, from a legal perspective, its loopholes are too many for it to actually convict harassers,” Majbour said.

Claudine Aoun, president of the National Commission for Lebanese Women (NCLW), explained that she believes the law itself is not problematic, but the main issue was its implementation. “To respond to any issues that might arise in implementing the law, NCLW is organising round tables and workshops with judges and public prosecutors across Lebanon to raise awareness about the law and proper ways of implementing it,” Aoun said.

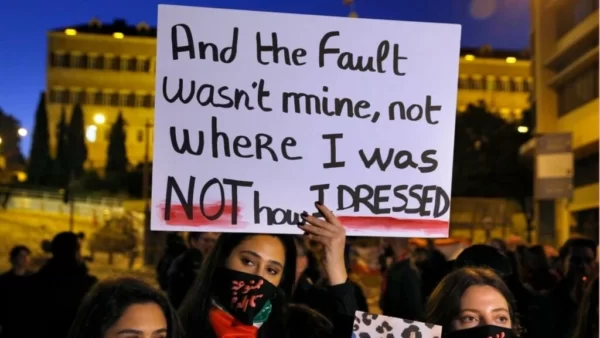

Barriers to speaking up

“I was six years old when my adult cousin decided to introduce me to a world I wasn’t supposed to know. It started with content of a pornographic [nature] and from there, it [escalated] into actions and forcing [me to do] things,” Noor Tofailli told FRANCE 24. “It only stopped because his mother one day walked in on him trying to do certain things. I was nine years-old at the time, yet she blamed me and kicked me out of the house.”

Tofailli repressed this memory for years and it wasn’t until she turned 19 that she shared her story in public.

“For the longest time, I felt guilty for doing something as a child and it took me a lot of time to realise that it wasn’t my fault. I shared my story to tell people that sexual harassment happens, and it is never the fault of the victim,” Tofailli said. “It is the fault of the harasser and the society.”

Because of her strong belief in a woman’s right to be free from harassment and her own experience as a child, Tofailli now works as a project manager with an NGO and trains people on gender-based violence. Through her work she hopes to redefine the narratives used to discuss harassment and support survivors by making sure they follow the right procedures to protect themselves after being harassed and report any incidents, if they wish to do so.

“We’ve reached a place in Lebanon where almost everyone acknowledges that sexual harassment is a problem. But there’s not enough knowledge on how, when exposed to harassment, women should act,” Tofailli said, stressing the importance of educating the public.

Salwa, who used her Twitter account to share survivors’ stories and expose harassers, identified judicial and societal barriers as the main reasons why people do not speak up.

“Women do not believe in the justice system in Lebanon, so they don’t report their cases to the authorities. They also fear societal blame, so they don’t speak up,” she said.

Majbour said it was important to speak up, not only to protect oneself but also other women, who could fall victim to the same harassers.

“Submit complaints, talk to a lawyer, speak up on social media … do anything, but don’t remain silent,” he said.

(*Lara is a pseudonym used to protect her identity.)

France 24

Comments are closed.